Perun, Slavic God of the Sky and Universe

Perun in Slavic Mythology

Perun was the supreme god of the pre-Christian Slavic pantheon, although there is evidence that he supplanted Svarog (the god of the sun) as the leader at some point in history. Perun was a pagan warrior of heaven and patron protector of warriors. As the liberator of atmospheric water (through his creation tale battle with the dragon Veles), he was worshipped as a god of agriculture, and bulls and a few humans were sacrificed to him.

In 988, the leader of the Kievan Rus' Vladimir I pulled down Perun's statue near Kyiv (Ukraine) and it was cast into the waters of the Dneiper River. As recently as 1950, people would cast gold coins in the Dneiper to honor Perun.

Appearance and Reputation

Perun is portrayed as a vigorous, red-bearded man with an imposing stature, with silver hair and a golden mustache. He carries a hammer, a war ax, and/or a bow with which he shoots bolts of lightning. He is associated with oxen and represented by a sacred tree—a mighty oak. He is sometimes illustrated as riding through the sky in a chariot drawn by a goat. In illustrations of his primary myth, he is sometimes pictured as an eagle sitting in the top branches of the tree, with his enemy and battle rival Veles the dragon curled around its roots.

Perun is associated with Thursday—the Slavic word for Thursday "Perendan" means "Perun's Day"—and his festival date was June 21.

Was Perun Invented by the Vikings?

There is a persistent tale that a tsar of the Kievan Rus, Vladimir I (ruled 980–1015 CE), invented the Slavic pantheon of gods out of a blend of Greek and Norse tales. That rumor arose out of the 1930s and 1940s German Kulturkreis movement. German anthropologists Erwin Wienecke (1904–1952) and Leonhard Franz (1870–1950), in particular, were of the opinion that the Slavs were incapable of developing any complex beliefs beyond animism, and they needed help from the "master race" to make that happen.

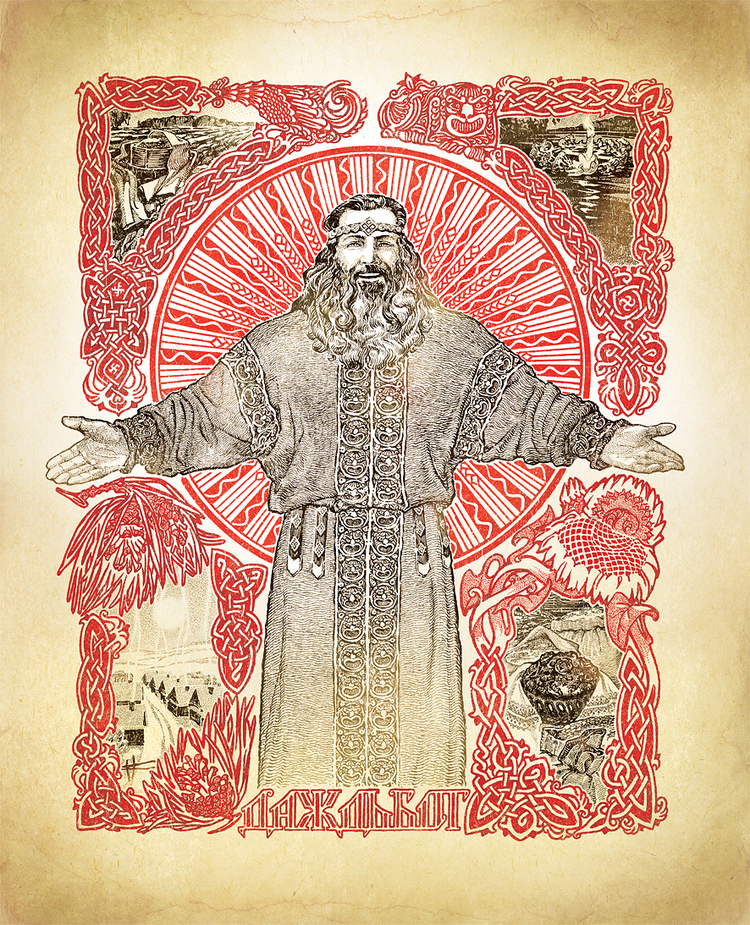

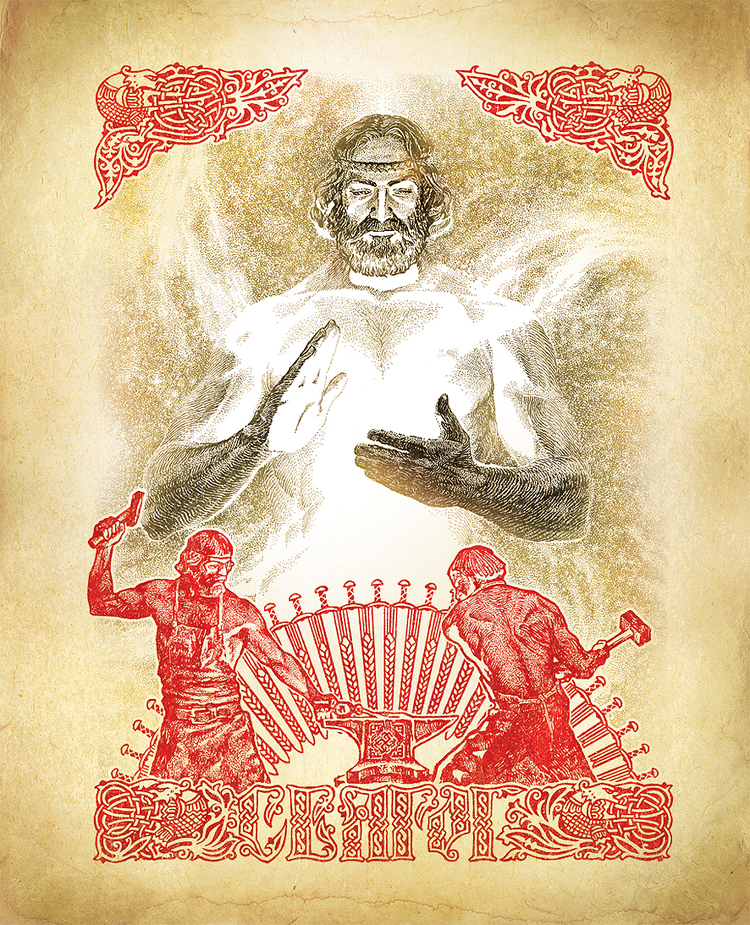

Vladimir I did, in fact, erect statues of six gods (Perun, Khors, Dazhbog, Stribog, Simargl, and Mokosh) on a hill near Kyiv, but there is documentary evidence that the Perun statue existed there decades earlier. The statue of Perun was larger than the others, made of wood with a head of silver and a mustache of gold. Later he removed the statues, having committed his countrymen to convert to Byzantine Greek Christianity, a very wise move to modernize the Kievan Rus' and facilitate trade in the region.

However, in their 2019 book "Slavic Gods and Heroes," scholars Judith Kalik and Alexander Uchitel continue to argue that Perun may have been invented by the Rus' between 911 and 944 in the first attempt to create a pantheon in Kyiv after Novgorod was replaced as the capital city. There are very few pre-Christian documents related to the Slavic cultures which survive, and the controversy may never be sufficiently resolved to everyone's satisfaction.

Ancient Sources for Perun

The earliest reference to Perun is in the works of the Byzantine scholar Procopius (500–565 CE), who noted that the Slavs worshipped the "Maker of Lightning" as the lord over everything and the god to whom cattle and other victims were sacrificed.

Perun appears in several surviving Varangian (Rus) treaties beginning in 907 CE. In 945, a treaty between the Rus' leader Prince Igor (consort of Princess Olga) and the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII included a reference to Igor's men (the unbaptized ones) laying down their weapons, shields, and gold ornaments and taking an oath at a statue of Perun—the baptized ones worshipped at the nearby church of St. Elias. The Chronicle of Novgorod (compiled 1016–1471) reports that when the Perun shrine in that city was attacked, there was a serious uprising of the people, all suggesting that the myth had some long-term substance.

Primary Myth

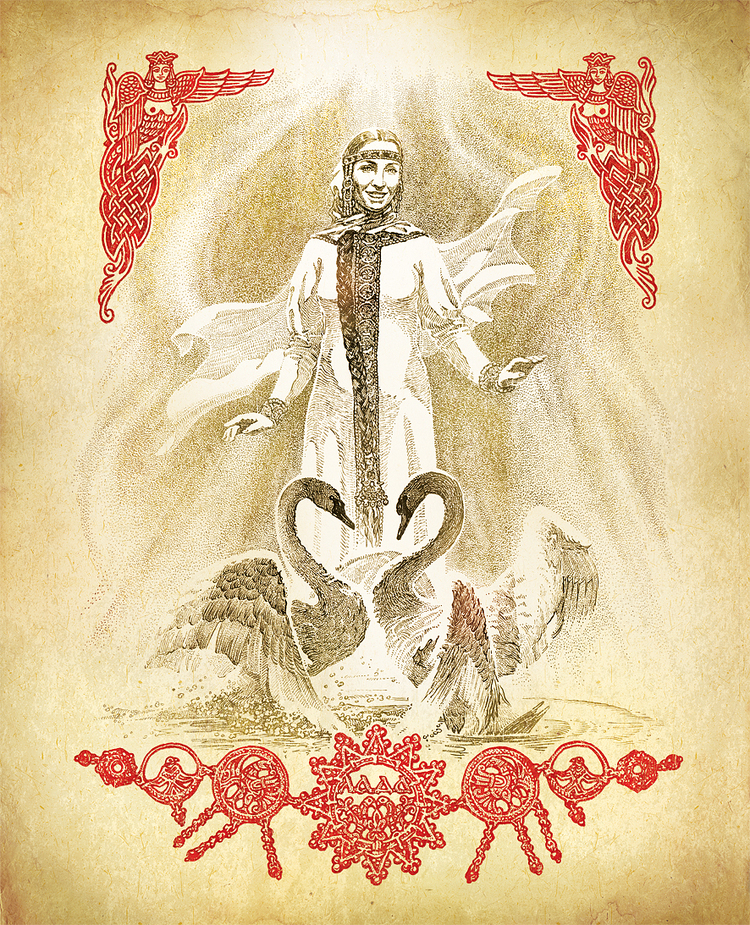

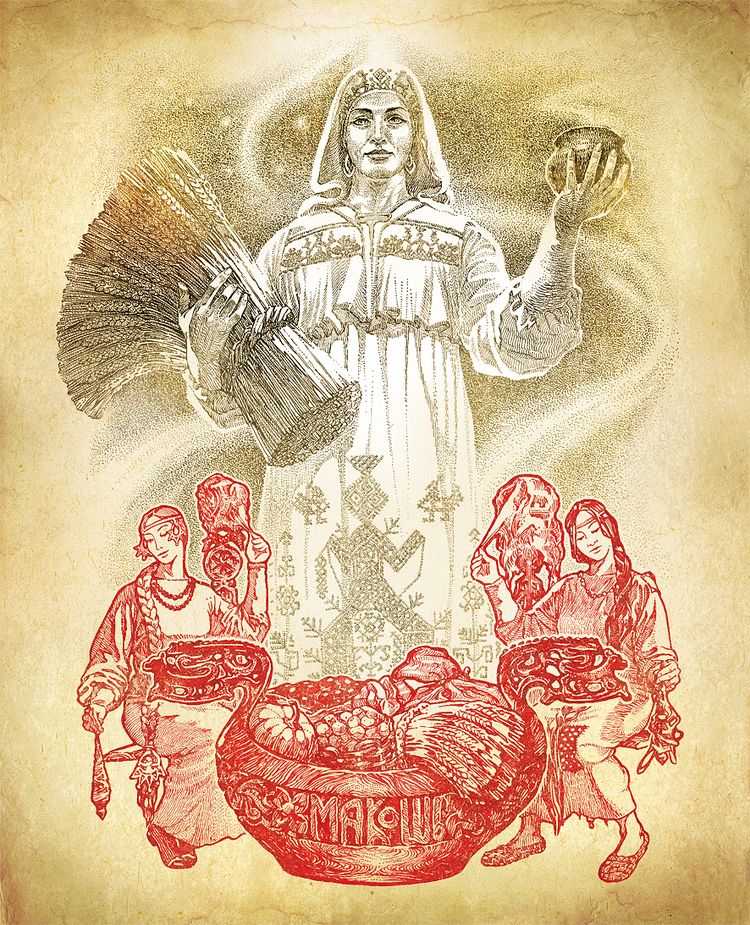

Perun is most significantly tied to a creation myth, in which he battles Veles, the Slavic god of the underworld, for the protection of his wife (Mokosh, goddess of summer) and the freedom of atmospheric water, as well as for the control of the universe.

Post-Christian Changes

After Christianization in the 11th century CE, Perun's cult became associated with St. Elias (Elijah), also known as the Holy Prophet Ilie (or Ilija Muromets or Ilja Gromovik), who is said to have ridden madly with a chariot of fire across the sky, and punished his enemies with lightning bolts.